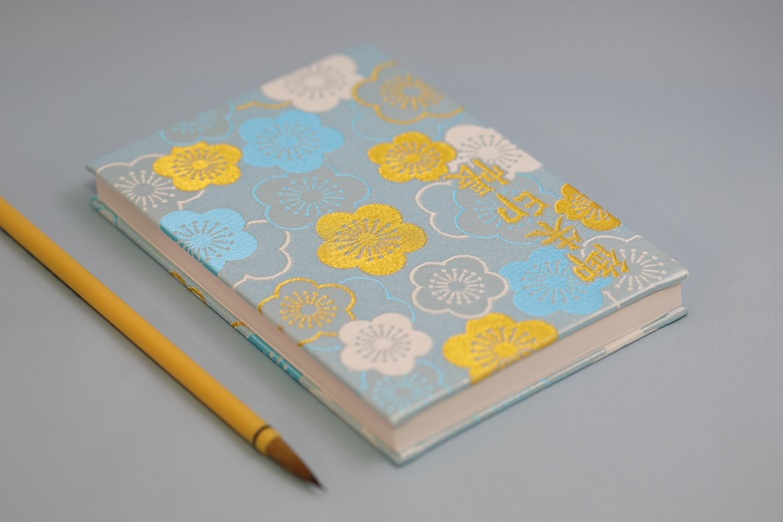

Across Japan’s shrines and temples, visitors often carry a small notebook filled with delicate ink strokes, bright vermilion stamps, and handwritten calligraphy. This notebook, known as a Goshuinchō (御朱印帳), is much more than a souvenir. It is a record of spiritual journeys, a personal art collection, and a cherished cultural tradition that continues to evolve in modern Japan. From ancient pilgrims to today’s young travelers, the practice of collecting goshuin—shrine and temple seal stamps—reveals a beautifully layered connection between faith, craftsmanship, and memory.

Origins of a Sacred Tradition

The custom of receiving goshuin began centuries ago, originally as proof that a person had copied Buddhist sutras—an act of devotion known as shakyō. Temples offered handwritten seals in recognition of this spiritual effort, marking a visitor’s dedication to Buddhist teachings. Over time, the practice expanded beyond sutra copying. Pilgrims walking long routes such as the Shikoku 88-temple pilgrimage or the Kumano Kodo began receiving goshuin as signs of their passage.

Although today goshuin are available to anyone who visits respectfully, their spiritual nature remains. Each stamp is written carefully by temple or shrine staff, combining the name of the site with the date of the visit and unique calligraphic elements. Unlike printed tickets or digital check-ins, a goshuin is created by hand in the moment—capturing time, place, and human presence in a single gesture.

The Beauty of Design: Calligraphy, Color, and Symbol

A goshuinchō becomes an art book in its own right. The bold black strokes of Japanese calligraphy contrast with the bright vermilion seals symbolizing the sacred boundary of the shrine or temple. Some feature decorative motifs such as lotus flowers, torii gates, guardian animals, or seasonal imagery. No two goshuin are exactly alike; what you receive in your notebook reflects the artistic style of the person who writes it.

In recent years, many temples and shrines have begun offering limited-edition seasonal or festival goshuin—celebrating cherry blossoms, autumn leaves, moon-viewing, or New Year’s rituals through special colors and designs. Some sites offer intricate kiri-e (paper-cut) goshuin or gold-embroidered sheets, blurring the line between religious stamp and fine art. For visitors, collecting them becomes an aesthetic journey as much as a spiritual one.

Modern Popularity: A Cultural Revival

While goshuinchō once appealed mainly to pilgrims and older generations, the tradition has experienced a remarkable revival among younger people in the past decade. Social media has played a major role; photos of beautifully decorated goshuin spread quickly, inspiring curiosity and travel. Many young Japanese now buy their first goshuinchō as part of weekend trips, solo journeys, or shrine visits during New Year.

Contemporary goshuinchō designs reflect this new enthusiasm. Beyond classic cloth-bound versions, bookstores and artisan shops now sell notebooks featuring watercolor artwork, traditional patterns, anime collaborations, or minimalist designs. This blending of tradition and modern creativity keeps the practice alive and relevant. For many, collecting goshuin has become a slow, mindful hobby—an analogue counterbalance to digital life.

A Personal Travel Diary

What makes a goshuinchō so meaningful is the way it records the traveler’s story. Each page marks a place visited, a day remembered, a quiet moment spent in nature or prayer. Even the walk to a shrine—the sound of gravel underfoot, the scent of cedar, the flutter of wooden ema plaques—becomes part of the memory preserved within the ink.

Unlike photographs, a goshuin captures the encounter between visitor and sacred space in a physical, intentional form. It encourages people to explore beyond famous sites, visiting smaller neighborhood shrines, countryside temples, and hidden spiritual spots. Over time, the notebook grows heavier—not just with ink, but with experiences.

A Living Tradition

In today’s Japan, goshuinchō stand at the intersection of spirituality, craftsmanship, and cultural nostalgia. They honor the past while adapting gracefully to the present, inviting anyone—pilgrim or tourist—to slow down and appreciate the quiet artistry of handwritten history.

To open a filled goshuinchō is to flip through a landscape of journeys: red stamps like lanterns, brushstrokes like flowing rivers, and dates that remind us of the paths we’ve walked. Whether treasured as spiritual keepsakes, artistic collections, or personal diaries, these notebooks continue to carry the gentle heartbeat of Japan’s sacred places—one stamp, one moment, one page at a time.